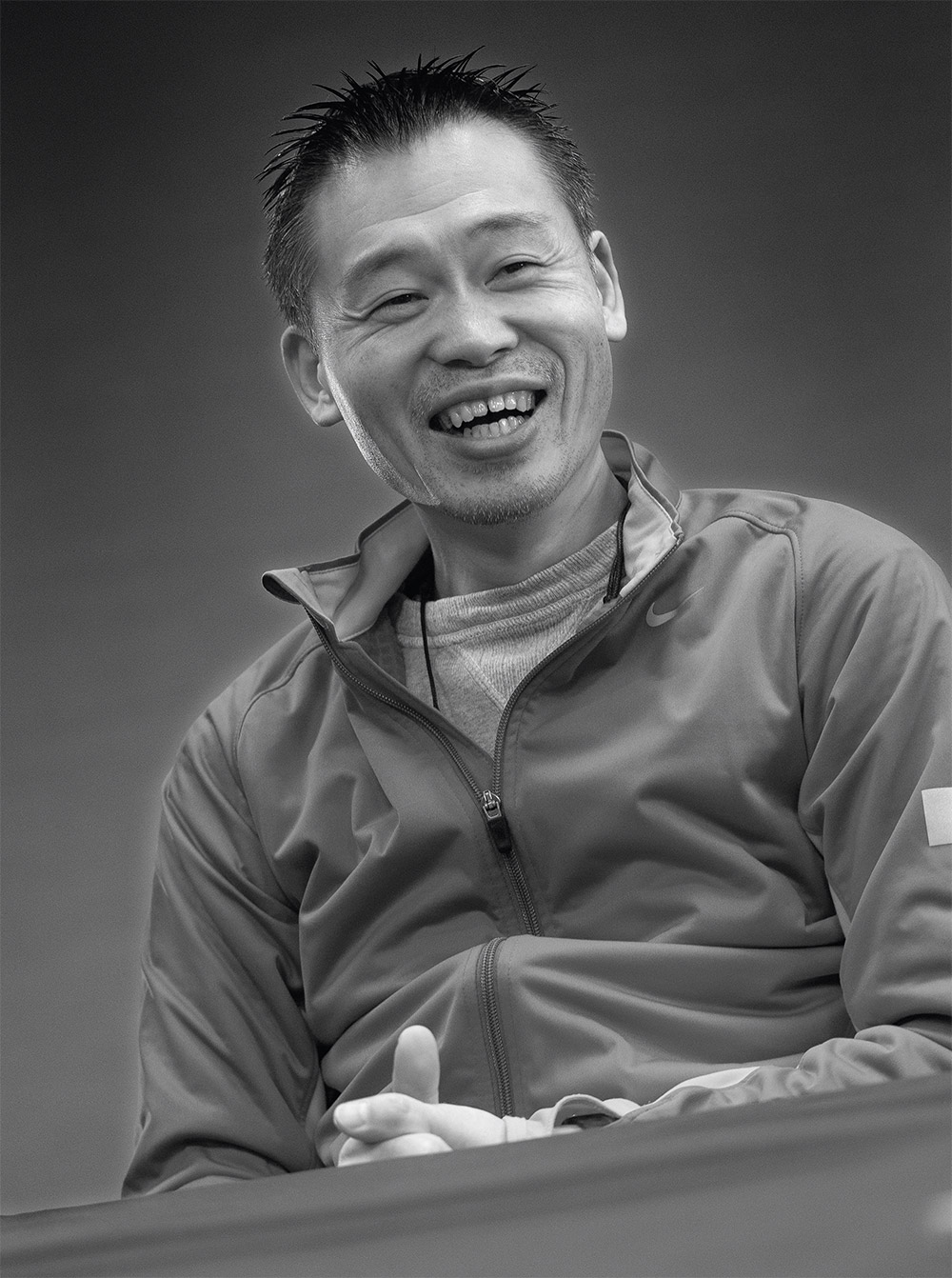

Keiji Inafune – His Life and Career

If one were asked to name the most famous, recognizable character sprite in the history of gaming, it’s likely that the original arcade Pac-Man and Mario from Super Mario Bros. would be battling it out fro the top spot. Behind them in third place, however, might be Mega Man.

Initially little more than one of the many releases Capcom produced for the NES, Mega Man was the story of a robot boy tasked with taking out six industrial robots who’d gone rogue. At the time, it was also just another project for Inafune, who served as a character designer on the game. While Inafune himself didn’t come up with the character of Mega Man—that credit went to Inafune’s superior at the time, Akira Kitamura—he’d go on to refine not only the Blue Bomber’s design, but also bring to life the six Robot Masters players would confront.

And thus, a collection of blue-, black-, and peach-colored pixels changed gaming, Capcom, and even Inafune himself. Of course, in the years since, the man who once thought he’d be making manga instead of video games became far more than just the father of Mega Man. While at Capcom, he went on to have a hand in crafting franchises such as Onimusha, Dead Rising, and Lost Planet. Then, after 23 years, Inafune left the company that served as his start in the industry and launched his own development studio, Comcept.

While Inafune’s recent roster of projects has seen him involved in some interesting collaborations with other Japanese developers, perhaps his most important partnership has come with an unlikely ally: his fans. Launched via Kickstarter, Comcept’s major new project, Mighty No. 9, will see Inafune give gamers around the globe something they’ve wanted for a long time now—a spiritual continuation of the Mega Man series.

Inafune will never be able to escape the legacy of the 2D action platformer he helped birth, and it may be surprising to some that he’d be so eager to walk that path once again. For Inafune, however, it’s a chance to finally fulfill some of the promises of his later days at Capcom—and the ability to do so on his own terms.

Mollie: You’ve been involved in gaming since the mid-’80s and helped create titles that, to this day, stand as cherished and exciting experiences for people around the world. What’s your earliest memory of gaming that got you excited or made you think that maybe, one day, you’d want to do this kind of stuff?

Keiji Inafune: Oh, man, I wonder… Video games, specifically?

Mollie: It doesn’t have to be a video game, really—it can be just games in general.

Inafune: I loved the board game The Game of Life when I was young. It was taking Japan by storm at the time. I think my first video game was a Breakout clone on the Nintendo Color TV-Game [Note: Nintendo’s pre-Famicom series of game consoles]. Before the Famicom came out, Nintendo’s consoles didn’t have interchangeable cartridges; they came with six or 15 game variations built in. The six-variation versions were obviously cheaper than the 15-variation versions. They had games like Pong. That was the first video game I played, and the first one I bought myself.

Mollie: It’s interesting that you mention The Game of Life, because that’s something that also came up as an early memory when I interviewed Hideo Kojima. For him, playing board games compelled him to make them, which then led him to want to make video games. Was the situation similar at all for you? While you were playing something like The Game of Life, were you thinking about rules and types of gameplay and other things that could eventually lead to video game development?

Inafune: The big difference between Kojima and me is that I draw. I’d much rather draw than type up a design document; I loved anime and manga rather than movies. In fact, I wanted to become a manga artist. I was just someone who happened to join a company that let me illustrate for games. I moved on to game design and production later. Really, my favorite thing is still drawing and creating characters.

Mollie: The era of anime and manga that happened in the years that you were growing up was a very important time for the industry. Artists and production companies were still finding their way in the medium, in terms of what fans wanted or what could be done when it came to storytelling and characters. What were some of the things from that era that would end up influencing you?

Inafune: Hmm… So many different artists influenced me when I was young. I was obsessed with Super Robot anime, loved the designs of the mecha, the silhouettes. I’m sure you can see the influence shows like Getter Robo or Mazinger Z had on Mega Man. Especially those works of Go Nagai. A lot of Go Nagai [Note: A legendary manga artist whose works include Mazinger Z, Devilman, and Cutie Honey].

Mollie: People often ask this, but it’s an interesting question: Why is Japan so in love with robots?

Inafune: Osamu Tezuka [Note: Japan’s “God of Manga”] influenced virtually all of Japan. After Astro Boy exploded in popularity, Japanese creators got excited about outdoing Astro Boy with ever-cooler robots. You might compare it to the influence of Superman in America and the proliferation of superheroes that came after. But in Japan, it was robots.

Mollie: Speaking of influence, there’s a definite difference in the mentality, style, and way of doing things between between people from Tokyo and Osaka. A lot of people in the West just see the Japanese way of doing things as being how Tokyo does things, but growing up just outside of Osaka, do you feel that had any specific influence on your particular style?

Inafune: Well, I do most of my work in Tokyo these days, but I live in Osaka. Osaka’s my home and my birthplace. It’s a very important place for me and was, of course, influential. I never moved to Tokyo because I never wanted to be a Tokyoite. I’m sure you’re aware of the Tokyo-Osaka rivalry. I want to succeed in Tokyo as a proud Osakan. [laughs]

Mollie: At what point in your life did you decide the things you wanted to do—being an illustrator, for example—were what you wanted to do as a job, versus just as a hobby?

Inafune: After I graduated high school and was about to enter college, I had to consider how I’d make a living. I knew I’d have regrets if I didn’t study something that was truly appealing to me. And if I failed? Que sera, sera. I seriously pondered what I enjoyed the most, and it was still illustration. I knew I had a talent for it that others didn’t. So, I went for that and ended up in the game industry.

Mollie: There’s this sentiment among Japanese people sometimes that, by age 25, you’re supposed to have your life figured out. You should be in the career you’ll have long-term, and you should be married—otherwise your hope for doing either significantly drops. Pursuing a job like illustration, however, that’s going after something that might not offer that stability. Did you ever get close to a point where you thought you should just give up and go for something more stable?

Inafune: At the time, I probably didn’t have much confidence at all. But as I said before, I wanted to live a life with no regrets. I’m the type of person who always plans ahead. Instead of cloning some hit title, I wanted to take risks designing games that had no precedent of success. I even applied that to the Kickstarter campaign. [laughs] People told me I should start to worry about designing Mighty No. 9 when and if the campaign succeeded, but they were wrong. It would have been too late. You don’t start to think of a career after leaving college, right? You have to work and make decisions before you enter. I guess that’s part of my “no regrets” policy.

Mollie: So how does all of this lead up to your getting a job at Capcom? And, when you got there, did you have any idea that you’d end up on the game-development side of the company, or were you only focused on the goal of being an illustrator. Did you think that might be the job you’d have for as long as you were there?

Inafune: I began the job thinking all my duties would be illustration, yes. But game directors and designers—as I’m sure you know—can be really late. If a director wants something a certain way, he has to communicate with artists, programmers, engineers. When a game designer takes too long in giving you a task, you start to get worried. This was already a problem on Mega Man 1. An illustrator’s job is to draw whatever the game designer wants, but if I had stuck to that, the game would never have shipped. I started presenting ideas with my character designs—what if this character attacked like this, or so-and-so boss used this pattern? It felt like a natural thing to do. I didn’t become a game designer because I wanted to; I had no choice. The game would be late. I quickly realized how efficient it was for a character designer to work on game design, too, and one thing led to another. But I’ve never called myself a game designer; I’m just an illustrator who can also do game design.

Mollie: How did it feel being at a game company at that point? Nowadays, the industry is this huge form of entertainment, but back then, gaming was still this much smaller field to work in. Was there a sense of excitement over what you were helping to produce, or was it just a job like any other potential career path?

Inafune: Oh, no—I thought it was a huge opportunity. Even if you hadn’t done so well in school, you could advance in the game industry. Men and women were given the same chances. This was extremely unusual in Japan. At a game company, the possibility of being promoted to a position above your boss was very real. I tried to make good products, make a name for myself, and keep climbing the ladder.

Mollie: One of your early things you worked on after getting to Capcom was the design of the Street Fighter character Adon. When you do work like that—you make a character, one little piece of a much larger game—is there any personal attachment you feel to that work? Or, when your contribution is that small, does it simply feel like part of the job, something you did and then moved on from?

Inafune: The Street Fighter team was nice enough to let me help out; I even did bug testing. The unfortunate thing about Adon was that he wasn’t playable. [laughs] The player couldn’t use everything I put into that character! I had to play Guile in Street Fighter II, since all the characters were new. Honestly, I have fonder memories of Guile, [who I didn’t even design,] than Adon. [laughs] Of course, I was happy when Adon became playable in the Street Fighter Alpha series. He was finally more than just someone there to get beaten up.

Mollie: Of course, you went on to work on Mega Man, a franchise that’s become immensely popular at this point. To this day, people still constantly bring up the series and the character in conversations with you. Do you ever feel like you’re in the shadow of Mega Man, and it’s something you’ll never be able to escape? Or will that just always be a part of who you are, and you’re able to embrace the fact that everyone knows you because of that little blue character?

Inafune: I’ve never really thought about it. I don’t mind if people ask me about Mega Man, but it’s not as though I want people to ask me about him. [laughs] Everyone has strong feelings about certain games. If a Mega Man fan identifies me with Mega Man, great. If they identify me with something else, that’s also great. I’ve never felt like I stood in Mega Man’s shadow, but I am thankful to him. And I’m thankful to Capcom, too.

Mollie: Are you surprised by how popular the series still is? It came out so long ago, and yet people, to this day, are still obsessed with the character. As a perfect example of that, just recently I repurchased Mega Man 2—a game I already own multiple copies of.

Inafune: Yeah. After all this time, the fact I’m sitting here 20-odd years later even talking about Mega Man surprises me. I never would have expected that. I’m honored I was able to help make a game that stuck in players’ consciousnesses. With regards to Mega Man 2, I think it’s a masterpiece. Even the people who made it think of it as a masterpiece. Working on a game that penetrates so deeply makes me happier than anything.

Mollie: As an illustrator, as someone to whom art is important, when you saw the American cover art for the first game, how did you feel?

Inafune: When Capcom USA sent us the package concepts, I was like, “They cannot be serious. This is a cruel joke!” I put in an official complaint, but the American side came back with “Americans respond to this kind of art.” It was culture shock, really. [laughs] I didn’t think American tastes were too different from Japanese, but I was told, “It has to be this way in America. This is what sells. If we use the Japanese box art, the game will flop.” I wasn’t very high up in the company yet, so I couldn’t push my opinion on the American box art too far. [laughs] Of course, years later, Americans told me they hate that box art, that it has nothing to do with the game. [laughs]

Mollie: So, you have things like the cover art, the change in names from Rockman to Mega Man, issues with the handling of the English version of Mega Man 8—how important to you, as a Japanese developer and designer who’s trying to sell his games to the world, is localization? What are the challenges between making sure a game can be appreciated in a different country by a different type of player, while still also being true to the game’s original intent?

Inafune: Well, localization of a game for its target market is an absolute must. With that said, I’m not too concerned about game titles, character names, or character designs created in Japan. After countless experiences with being ordered to change things, now I consider the bigger picture. If I were still making games with the intention to release only in Japan, things might be different. But at this point in my career, I’ve had lot of experience with localization, and I understand why certain things work and others don’t. These days—especially now that I have my own development company—I take a comprehensive, worldwide approach from the very start. I try to minimize potential localization issues as much as possible.

Mollie: On the subject of the relationship between the West and Japan in the gaming world, you’ve come to be seen as a prominent figure in the conversation about the good—and bad—points for the game-development practices and traditions from each side. Were you put into that place by your own decision, or did you just sort of find yourself pushed into that decision due to a natural expression of your opinions?

Inafune: Hmm… I think I started talking about it because nobody else was. As a Japanese game developer, I can see the aspects of the Japanese approach that work well, but it’s also easy for me to criticize those that don’t. I believe I can also recognize positive aspects of the Western approach. Most Japanese people hide their true feelings beneath a façade of politeness, so maybe I’m rare in that regard. If my speaking out somehow improves Japanese game development, I’ll be happy. Journalists have come to know I answer straight and honestly, so they ask me the hard questions. I believe what I’m doing is of service to the Japanese game industry.

Mollie: Have you had anyone in Japan break that level of forced politeness and criticize you for attacking the Japanese games industry? With how heated and passionate some obviously get regarding the conversation, it’s easy to imagine that at least someone—especially a colleague in the Japanese game-development community—may have accused you of betraying them.

Inafune: No typical Japanese person would say it to my face, but I’m sure they talk about me behind my back. “What the hell is Inafune ranting about? The Japanese game industry isn’t dead!” People who worked their damndest only to see their company actually die say this stuff. Sure, some of them might not like me, but I have a tough personality. I’m used to being loved and hated. [laughs] People who hate me will hate me; I don’t care. I feel the Japanese put far too much emphasis on being “liked.” Everyone has good points, everyone has flaws. In Japan, the basic mindset is that you’ll be shunned if you dare speak your mind. That might work inside Japan, but it won’t fly globally. The game industry is a global business; I think traditional Japanese attitudes are a detriment to competition. If I’m able to compete internationally at the cost of drawing hatred, I couldn’t care less.

Mollie: Your former employer, Capcom, has put a focus on having East-West collaborations on game projects that previously were typically handled solely by Japanese teams. Is the future of Japanese game development working with the West? Or do Japanese developers simply need to do a better job of reminding players in the West why their games as worth playing?

Inafune: Hmm… I wonder. I’d like to say it’s possible, but it might not be. I don’t think Japanese companies should rely entirely on Western developers. East and West should join forces. Unfortunately, a lot of Japanese publishers—when they say they’re working with outside companies—simply throw IPs at Western developers and hope something worthwhile comes back. I would never do that. Both Western and Japanese developers have their deficiencies, but together, we can make up for them. My ideal is to create an environment in which Western and Japanese developers can truly collaborate. It wouldn’t just benefit Japan; it would benefit the entire game industry.

Mollie: Recently, I was playing Aksys’ English-language release of Idea Factory’s PSP visual novel Sweet Fuse: At You Side, and there you were in the game, playing the role of my uncle. And then, in another of their games—Hyperdimension Neptunia mk2—your giant, real-world head can be called up to perform attacks in battle. How do cameos like that happen?

Inafune: Well, the president of Idea Factory came to me in person and sort of sheepishly asked if I’d be willing to participate in his crazy cameo ideas. [laughs] In any other case I’d have turned it down, but it was such a unique concept. I root for anyone trying something new and different, so it was a simple “yes” for me. The collaborations with Idea Factory were something I couldn’t have done while at Capcom. It would have tarnished the company’s image, and I’d have had to go through getting a lot of approvals. My giant face in Neptunia? Totally impossible! [laughs] As a private individual, however, I only had to say yes. The cameos were amusing, but there was no real benefit in the deal for me. [laughs]

Mollie: You design games, you create characters for them, you produce them, and sometimes you even star in them. But would you consider yourself a “gamer”? Do you also play games, or do you see yourself more as the person who’s there to create the games that others play?

Inafune: I don’t know. [laughs] I’m not really a part of the video game fan community. And a game creator… I’d rather be known simply as a “creator.” I don’t limit myself to video games; I pursue a wide range of creative works.

Mollie: What’s in store in the future for Keiji Inafune the creator, and for your company, Comcept?

Inafune: Hmm… The fact we were able to create a new IP thanks to Kickstarter was a big deal for me, and for us. I’d say our future is creating IPs that we retain the rights to. We’re already bringing our own IP to mobile platforms, and we have Mighty No. 9 coming up. If we had a plan that would fit a Kickstarter campaign we’d do it again—I’d have no reservations in going that route again. If another method were a better fit, we’d go in that direction.

Mollie: You’re originally from Kishiwada, a city in the southern portion of Osaka prefecture, and one of the things that Kishiwada is known for is its Danjiri Matsuri. [Note: A type of street festival in Japan where large wooden carts, elaborately designed to resemble shrines or temples, are pulled by festival participants.] If there were a Keiji Inafune–themed Danjiri Matsuri held in Japan, what would it consist of?

Inafune: Danjiri are huge and heavy, right? Carrying and running with them takes a lot of manpower. It’s a bit like game development. Just as an example, tons of people are working on Mighty No. 9. The more people surrounding your danjiri, the better you can maneuver it. I’d love to have a huge mass of compatriots supporting the Inafune danjiri. We could do incredible things together. My danjiri is a tough one to shoulder, so the talent carrying it will have to be dedicated. [laughs]

Mollie: Japanese cities are often known for their signature foods, and two of the most popular in Osaka are takoyaki [Note: fried octopus dumplings] and okonomiyaki [Note: a savory pancake-style dish]. Which would you pick as the “true” Osakan food?

Inafune: You can’t really compare takoyaki and okonomiyaki. Takoyaki are snacks, but okonomiyaki is a meal. I don’t think Osakans ever pit the two against each other. [laughs] It’s not like there are separate “takoyaki factions” and “okonomiyaki factions.” We love both. I love both. [laughs] When you just need a bite, takoyaki. When you’re starving, okonomiyaki. [laughs] I don’t think it’s even possible for someone from Osaka to choose one over the other. I sure can’t. [laughs]

Mollie: If you were to be a robot in the Mega Man</i >series, what kind of “-Man” would you be, and what would be your power?

Inafune: Oh, I’m definitely Mega Man. Mega Man’s power is the ability to absorb every other Robot Master’s power, right? I think that’s my specialty. I have a knack for learning others’ powers. Let’s say I visit a Western developer and see the new tech they’re using. I’ll “absorb” that and bring it back to Japan. I’ll play another developer’s console game and absorb the interesting mechanics. I’ll play an innovative smartphone game and absorb its premise. Mega Man can’t win all by himself; he has to learn and grow to succeed. I think that’s me.

Mollie: Then, if you are indeed Mega Man, which of his potential love interests would you settle down with: Roll or Tron Bonne?

Inafune: I, uh… [laughs] Well, Roll is gentle, meek, and kind—she has very Japanese traits. She’s much more the traditional Japanese girl. Tron is more…international? [laughs] If I had to choose, probably the international type. My real-life wife is very Japanese, you see. [laughs] But, maybe I’d go for the one who isn’t as traditionally Japanese.

Mollie: We talked about your cameos in titles like Sweet Fuse</i >and Hyperdimension Neptunia, but what’s the one game or series you’d most love to show up in?

Inafune: Oh, man… Mario? Yeah. The entire world plays Mario games, I’d be an international celebrity. [laughs]

Mollie: If you’d ended up becoming a manga artist instead of a game creator, what kind of manga would you have created?

Inafune: Hmm! I really love every genre of manga—giant robots, zombies, whatever. I don’t think I’d have worked in one specific genre. I don’t make games in one specific genre either, so…I’d probably have drawn whatever I felt like on the day. [laughs] Osamu Tezuka—the most respected manga artist in history—drew stories in every genre imaginable. I wish I could’ve done that.