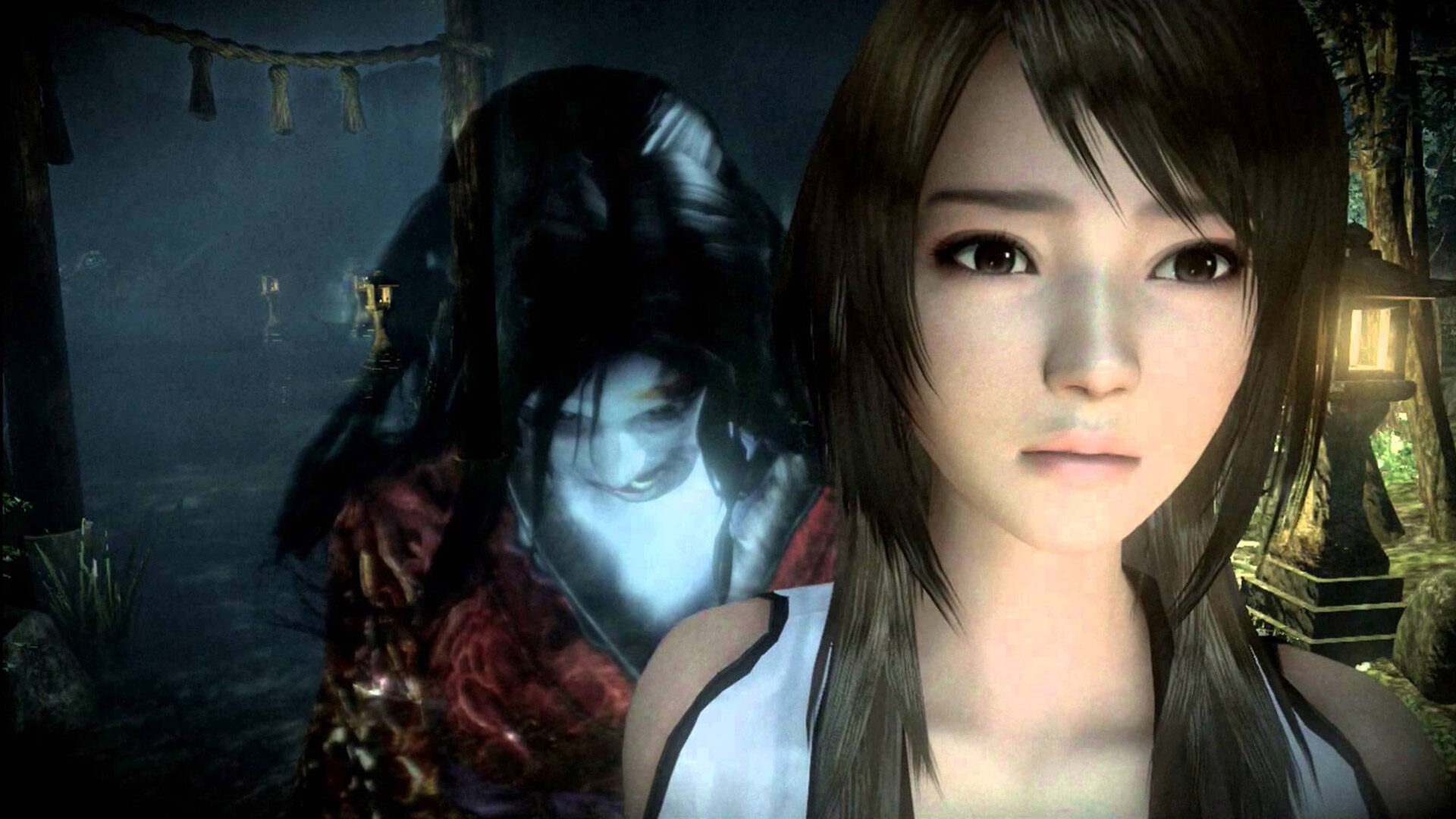

Makoto Shibata + Toru Osawa – Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water

When running down a list of the top horror games out there, I’ve long included the Fatal Frame series. The first of its offerings mixed together the physical threats of Resident Evil with the more psychological scares of Silent Hill, but it was the second chapter—Fatal Frame II: Crimson Butterfly—that truly cemented the franchise’s place for me.

When the future of Fatal Frame switched focus to Nintendo’s platforms, I’ll be honest: it was initially something of a surprise for me. That surprise turned to disappointment when the fourth chapter of the series, Fatal Frame: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse, ended up staying stuck in Japan. Thankfully, its follow-up—Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water—not only returned to seeing international release, but also developed upon new gameplay ideas using the Wii U’s GamePad that showcased how the Nintendo connection could provide some freshness to the series.

In honor of its recent launch here in the States, I had the chance to ask some questions to Koei Tecmo’s Makoto Shibata, Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water‘s director, and Toru Osawa, the game’s co-producer on Nintendo’s side.

Mollie: What is it do you think that has made the Fatal Frame series so popular among fans of horror games?

Toru Osawa: I suppose it comes down to horror game fans in the West praising how its atmosphere and presentation is less about offering dynamic “jump scares” with its depictions of violence, and more about the static “shivers down your spine” feel. That’s the same reason why Nintendo, a company that didn’t deal much in horror in the past, wanted to provide their support to this title.

Makoto Shibata: There aren’t many titles in the horror genre that deal in this sort of spiritually-oriented fear. I think the strength of the series lies in the unique experience it offers, something you can’t find in any other game.

Mollie: Japanese horror is very different from Western horror. What elements of Japanese horror do you think make the genre so scary, and why is Japanese horror more psychological versus physical?

Shibata: Japan’s kaidan ghost stories and classic horror films deal a lot in psychological horror. You could say that this game rides on the tradition of this Japanese horror content.

The ghosts that appear in these stories always belong to those who were physically weaker, such as women or children. This sense of physical weakness helps to emphasize the tragedy and sorrow that drives them. It’s a very psychological thing, and you feel like you’re powerless to fight back against the intensity of their grudge. It’s the total opposite approach from violence-oriented fear, and since we’re all used to hearing Japanese ghost stories here, it’s very familiar territory to us.

Mollie: The Fatal Frame series often takes place in more rural or desolate areas of Japan. When I lived in the country, I often found those kinds of places somewhat creepy at night. Why do you think these kinds of locations work so well as settings for Fatal Frame, and what are some of the natural or manmade environmental elements that you think help create the scariest setting?

Shibata: In Japan, even in the more rural or desolate areas, there’s often a lot of evidence left behind that something used to be there. It’s these places, where you can feel the memories within the land, which work well for this game. I think the scariest situation you can have in a horror game is walking around this area where “something used to be,” imagining for yourself what it could have been.

Mollie: It’s easy to come up with a new idea for a game and have it feel fresh, but much harder to have that idea still feel unique after four sequels. What were some of the ideas and gameplay elements—other than water—used in Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water that help it stand out from the previous games?

Shibata: With this game we implemented ideas like having the Wii U GamePad serve as your Camera Obscura, as well as the ability to touch ghosts in order to see their cause of death and the powerful emotions they want to leave behind. The element of reaching out in order to pick up items existed in the previous game, but now you can use that same motion on ghosts and living people as well.

These ideas become an element in the battles where you use the camera as well, but they play a bigger role in the story, where the main characters gradually learn the memories of the dead and the secrets behind the people around them.

Mollie: Then hitting on the idea I made you skip, one major element to Maiden of Black Water is water itself. Why can water cause such fear in us? And how did you use it in the game to express fear?

Shibata: I think there needs to be a level of moisture in the air in order for ghosts to appear. I was in Los Angeles in the summer, and the experience made me really feel like “I doubt I would run into any ghosts around here”. Then, when I went back to Japan and immersed myself in the kind of summer humidity you only see in Japan, it made me realize once again how much of a necessary element it was. When you’re surrounded by moisture or water, you’re surrounded by something larger than yourself; the boundaries between you and the rest of the world grow ambiguous. I had the idea of beings you can’t see reaching out to you through that moisture, and that’s where the theme of water came from.

Thinking about it, moisture was an important element in previous games, too. One thing we focused on was to have this artwork where it seemed like the moisture of your environment was coming at you through the screen.

For this game, we explicitly tried to use water in all its assorted forms. We set it up so that there’s always water someplace onscreen, including the water droplets that stream down in menu screens where you’re reading text and so on. Then there’s the rain, lakes, rivers, and fog you see in the stages. That applies to the baths as well. Water and enclosed boxes are two themes in this game, so your character has to enter a bath at one point.

Mollie: The Camera Obscure is such an integral part of the Fatal Frame series, and with the Maiden of Black Water coming out on the Wii U, being able to use the Game Pad as your camera is such an immersive element to the game. Could you give some thoughts on what you think of this feature, and how it changes the game for players beyond the previous games? And were there any other ways in which the Wii U allowed you to do things you never could before in the game?

Osawa: I think a lot of people’s first impression of the Wii U GamePad was that it was camera-like, both in function and in shape. It was obvious to us that something like Fatal Frame, where you’re using the Camera Obscura as your weapon, was the most suitable kind of game for this. We can also display images on the GamePad screen that don’t show up on your TV screen, which I think offers different types of fun to people playing it and people objectively watching them play.

Shibata: The Wii U GamePad gives you a very natural way to survey the game world, and looking at the GamePad feels like you’re peering into a camera. It’s the most suitable gadget for boosting your sense of immersion in the game, and when I looked at the Wii U’s hardware overview, I was struck by a sense of mission, like we had to get Fatal Frame on there. The experience is important when it comes to horror games, after all.

Still, I came to realize that playing like this for a long time would tire you out, so we made efforts to keep it easy to play—letting you use the stick to aim, as well as gyro control, dividing it by chapters to provide natural break points, and auto-saving at frequent occasions.

Mollie: Some of the best horror games have a delicate balance between the scary things you can see, and those that you can’t—such as noises or things that happen without your knowing at first. How do you decide when to scare the player with what might be called a “jump scare” and when to instead use something more subtle or non-visual?

Shibata: I follow something that I call the “law of nightmares”. When you’re asleep and having a nightmare, things that you “absolutely don’t want to happen here” flash across your mind and appear vividly. So, oftentimes, I decided on the scary points of the story based on the dreams I had while making the game.

During my dreams, I try to remember what I saw, as well as what kind of sounds I heard afterward. I also count my breaths, so I can recreate precisely at which breath some bad event or another happened.

For this game, though, I don’t think players will feel all the emotions I intended, exactly as planned. This game’s focus is on ease of control and fun battles; we did things like offer more freedom and increase your running speed. These are things that Nintendo was very fastidious about.

Instead of strictly adhering to every rule of the horror game genre, our concept here was to treat it like fast-forwarding a DVD, letting players skip through scenes as they like and play more leisurely through the parts that strike their interest.

For example, this game features shades that you can see, the past shadows of missing people. If you chase after these shades, you’ll never get lost. If you take your time instead, though, exploring your surroundings as you follow the shade’s trail, you’ll find more items and scary elements waiting for you.

The pacing that’s usually meticulously created by the designers is made more ambiguous here, which may make it seem like it doesn’t have all the elements of the previous title as a horror game, but after the test-play cycle, it played well. In fact, some of the feedback we received said that it was just the right level of horror, enough to make you want to keep playing.

With previous games, I’d receive feedback that the scariness made people stop playing midway, and I went with this approach because I want to find some way to have them play through to the end.

Mollie: I’ve read talk that a male character has been contemplated at times for the series, but so far, all Fatal Frame games have had female protagonists. What do you think a female character is able to bring to the game that a male character cannot?

Shibata: As mentioned earlier, Japan’s traditional ghost stories often deal in the grudges of physically weaker people, such as women and children. These are not issues that can be resolved by a male hero using purely physical means. The fact that you have women who migh not be as physically strong serving as the main characters in this game provides an indication that you can’t solve the mystery on Mt. Hikami with physical force.

Also, in order to defeat the spirit of the woman who serves as the final boss (in other words, to put a stop to her and resolve her grudge), you have to work with her in a sympathetic manner. The main character is at the waypoint between the real world and the world of the dead, wandering in the crevice between life and death, and that’s what enables her to bring the story to a conclusion. It’s best if the hero is placed in the same circumstances as the last boss here, so having a woman in this role was preferable for story purposes as well.

Mollie: Video games are often made to make us feel powerful, or happy, or excited, yet horror games are focused on making us feel weak, and helpless, and terrified. Why do we enjoy playing such games? And, as a developer, what is it like to create a horror game? How do you get into the mindset to make one, and what do they let you express that you might not be able to in other genres?

Shibata: I first started designing for this game series in the year 2000. At the time, I imagined that games would be more than just these fun, exciting, cool, flashy things that stimulated your emotions in positive ways; I thought they’d stimulate different parts of your mind in other assorted ways. With this game, our aim is fear, the most primordial of these emotions, and in particular the kind of fear that stokes your imagination. No matter how far graphics advance in the future, it still won’t be a match for the images in your mind that scare you. I wanted to make a game that stimulated that kind of thing.

Another aim of mine here was to make you feel the things that you can’t see. That’s something different from just graphical improvements. When I occasionally run into a ghost, the atmosphere and sound I hear just before that encounter are totally unique things. I wanted to recreate that in the game and help bring that feeling to players. The way the video-game genre lets you actually move a character around lets you express a virtual space better than with films or novels. It’s that spatial design that really gets unleashed with horror. You can make a game where it’s scary just to wander around the area.

Finally, I wanted to create a game where the fear you felt during gameplay stuck with you in daily life, after you finish playing. Maybe you’d feel someone’s eyes upon you, or tiny noises would sound a lot louder.

I think that kind of experience is special. The familiar sights around you suddenly look far different from the everyday. That’s because you’ve had an experience where you’re closer to these things you can’t see, and to death itself.

That’s a scary thing, but all of us have a moment where we’re fascinated by death. I think that’s what makes Fatal Frame fun to play.

Mollie: If you took a photograph in your home and a ghost appeared in the photo, what would be the scariest thing for you personally to see in that photo?

Osawa: Something that made me think my future would be unhappy. If I saw myself or my family after death, I think that’d be pretty scary.

Shibata: I’ve had this dream several times, but the sight of my own funeral. The attendees’ faces are all hidden, but the moment the picture’s taken, they turn around, and for some reason all you can see is their eyes.