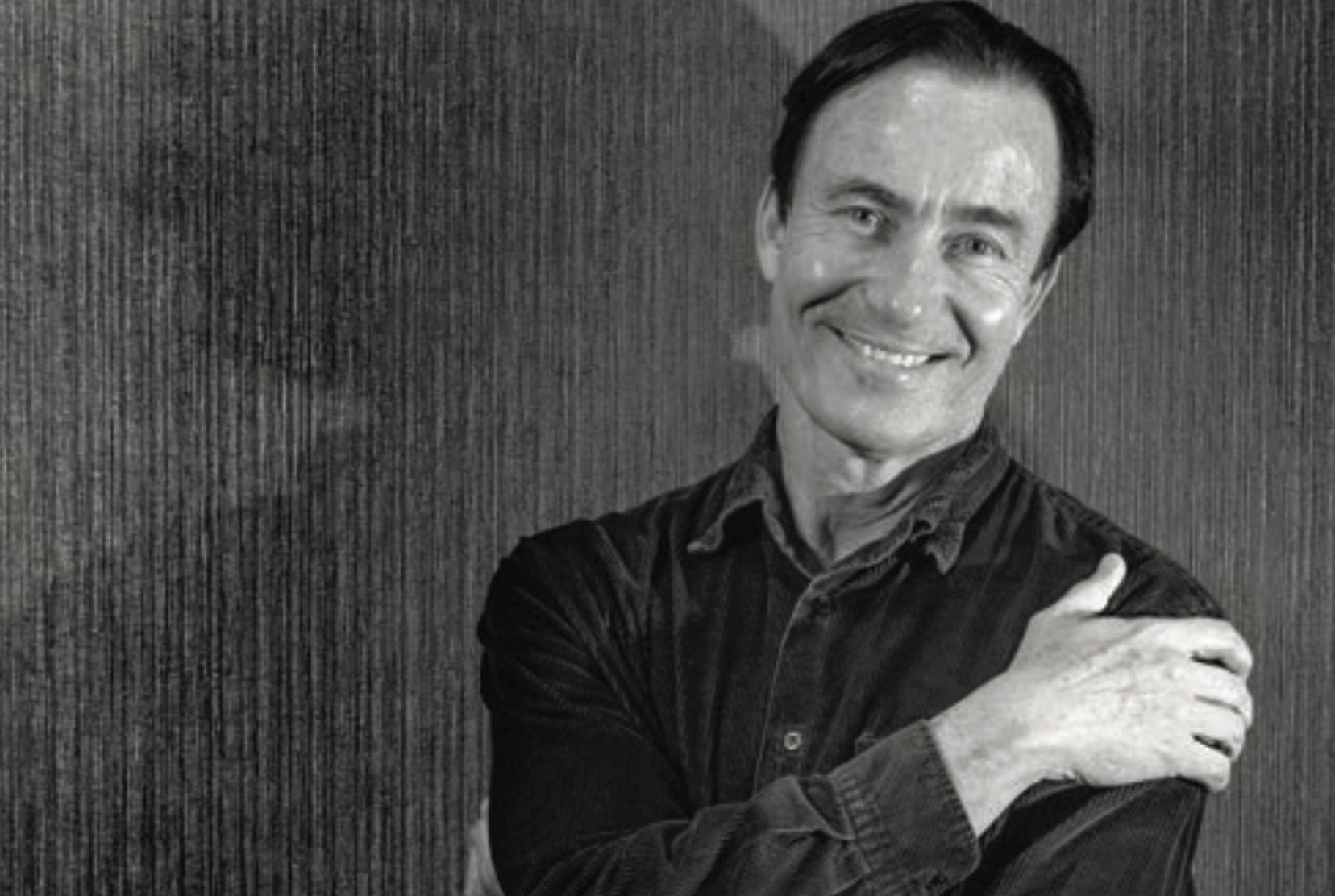

Trip Hawkins – His Life & Career

When looking toward the world of video games, one might be able to say the same of Trip Hawkins. He was there at Apple, in those early days, working alongside Jobs and Steve Wozniak to help bring about the home-computing revolution. Later, he founded The 3DO Company, one of the pioneers in the gaming hardware market, and pushed the idea of a home console that could bring consumers a wide array of multimedia options just as easily as it could play games. He launched Digital Chocolate, a development group focused on pushing mobile gaming forward long before every man, woman, and child played bird-based entertainment on their smartphones and tablet devices.

Oh, and then there was another little company that Hawkins can claim responsibility for: Electronic Arts.

“I think the thing I’m best known for is being the founder of Electronic Arts, and I’m happy for that, because EA is like one of my children,” Hawkins says when asked what will be most remembered of his legacy. “It’s important, to me, to have people remember that I did that.”

Without Hawkins’ love for sports-themed tabletop games as a child, there may never have been NBA Live. NHL Hockey. Madden NFL. Hawkins’ drive to one day making a proper football videogame helped create the biggest player in the sports genre.

Like Apple, his claims to fame are many, his contributions to our hobby far-reaching and impactful. Over the years, however, while Hawkins’ passion for video games hasn’t waned, he’s set his sights on a new goal: not just making gaming better, but making humanity better through gaming.

Mollie: You’ve said that you’ve had a passion for board, card, and tabletop games since an early age, mentioning things such as Strat-O-Matic and Dungeons & Dragons. What’s interesting is that two people I’ve interviewed, Hideo Kojima and Keiji Inafune, both listed very similar ways of getting into gaming.

Trip Hawkins: Huh. Interesting.

Mollie: What is it that makes some people play board games and say, “You know what? I want to take this somewhere else. I want to be making the rules instead of just playing them.”

Trip: I think what you’re talking about here is people that have proven, in the game industry, to be creative and imaginative. For someone who has a lot of imagination, if they encounter a game like D&D in their childhood, they’re going to notice the incredibly powerful fantasies that you can have with a game like that, and they’re also going to notice the feeling of authenticity. You just can’t get away from the power of those two elements, in that you get a chance to be an epic hero in an epic situation.

For me, sports games were a bigger deal, but I don’t think, as a child, I really objectively thought I was going to be Willie Mays. [laughs] I think the power of authenticity was equally valuable, because I felt like I was doing something really sophisticated that only adults had access to—and I got to do it as a child. I got to make adult decisions in a situation that seemed like an authentic, adult situation.

Mollie: Were board games the sole reason you got into video games? Or were they just the first of many steps?

Trip: No, that was it for me. I think somebody today could start out playing video games, but frankly, those devices and games weren’t available to me when I was a child. The big media choices available then were television, radio, reading, and board games. I was playing board games, and I realized that my friends wanted to watch TV.

Then I heard about computers. At that point, computers weren’t yet available to consumers, but I was thinking, “Oh, that’s how we’re going to do this. We’re going to basically take the administrative burden of playing a complex game like D&D, and we’re going to put it in a computer. And then we’re going to put pretty pictures on the screen and make it look and feel like television.” I was just imaginative enough that I could see that before it existed. And I saw it, what, at least a decade before it existed? I knew it was going to be good, and I knew it was going to be worthwhile. It was pretty easy, at the time, for me to say, “Yeah, that’s what I’m going to do.”

Mollie: Can you ever really make the true Dungeons & Dragons experience through a videogame, or does that always have to be an in-person, at-a-table kind of experience?

Trip: Well, I bet you can, but nobody’s done it yet. What I would say is that the best thing about D&D is the social community from the group of players sitting around the same table and acting out their characters. I still play it, by the way. [laughs] Mostly, now, I play the Dungeon Master for one of my children who wants me to help when he’s playing with his friends.

Frankly, to me, the most entertaining part of D&D is when the party first comes together in the town or in an inn. There are all kinds of fun little subplots you can invent, so the social interaction, sitting around the same table, and the humor of the way that the characters are creatively expressing themselves, that’s the most precious part of it.

Now, if you look at how it migrated into computers, I certainly enjoyed playing games like The Bard’s Tale and that early generation of RPGs like Ultima. And then when it went online, it went back to being multiplayer, so today’s games, like Lord of the Rings Online or D&D or various other brands of it, my friends that I grew up with, the ones who never had children are really avid players of those games. [laughs]

But those games are, in my opinion, too frenetic. It’s all about the battling that’s going on. And, yeah, players have their headsets on, and they’re talking to each other, so there’s that social dimension. They’re doing it together. And there’s some humor in that, but they don’t have the quieter, more contemplative, more creative moments that, I think, you have in a genuine game of D&D.

Mollie: At what point did you experience your first videogame? How did you make that jump between knowing what gaming is, in terms of tables and books and dice and things like that, and suddenly saying, “Wow, there’s this whole other universe of gaming that’s about to begin”?

Trip: I was in high school in the early 1970s, and my father had worked with the guy who turned out to be one of the technical titans of the first generation of the videogame industry. His name is Lane Hauck, and he’s a really brilliant guy. When I first met him, he was developing an interest in computers as a hobby. Lane had a KSR-33 [Note: An electromechanical teleprinter from Teletype] and hooked it up to a PDP-8 kit [Note: A commercially available minicomputer from Digital Equipment Corporation in the 1960s], and then he invented a game that he called MOO, where you could tap in four-number digits on the KSR-33, and then it would spit back an answer. You’d try to guess a four-digit number, and it would tell you which numbers you had right and which numbers you had in the right slots.

Mollie: Kind of like the old Mastermind board game.

Trip: Exactly. Mastermind came along later, but yes, same concept. He was probably the first guy to program that kind of game on a computer, and I’d already heard a little bit about computers and was imagining these possibilities, so it was an important stepping-stone for me to have faith and belief that this was the future.

And then, of course, I go off to college a year or two after that, and I had access to a mini-computer for the first time. I remember, in one of the computer centers—the Aiken Computer Lab at Harvard, where Bill Gates and I probably crossed paths without knowing each other at the time—there was a big cabinet with a display in it that could run a game kind of like Computer Space, the first product from [Pong co-creator] Nolan Bushnell. I think some guys had basically copied it and made it run there. That was enough for me. I didn’t have to see very much to have faith that, yeah, we can do this. This is going to happen. It’s just a question of exactly what form it’s going to be and when the technology’s going to steadily get better.

Mollie: How were video games accepted in those early days?

Trip: I think when something new shows up, you have a group of hobbyists that adopt it, and then you have the mainstream, which is likely to have a rejecting attitude about it. Every new medium has gone through a hazing period. Still, to this day, I don’t think the medium is really that well understood, and I think it gets picked on a lot more than it should.

I remember in the very early days of EA in 1983, we made a game, Hard Hat Mack, where you had a character that was working on a construction site. It was kind of a platformer, and one of the characters that chased him around was an OSHA inspector. It was just a little joke, but [California state senator Dan McCorquodale] here in the San Francisco Bay Area thought, “Hey, I’m gonna get some publicity by making a stink out of this.” And the next thing you know, I’ve got the media calling me, saying an Emporium-Capwell store had decided not to sell the game because of pressure from this politician.

Mollie: Wow.

Trip: I know it’s kind of shocking to even imagine a department store like Emporium-Capwell selling video games, but they’d been one of the first mainstream retailers to carry Apple, and then, for a period of time, they were pretty focused on it before the specialty-store business really took off. It was one of the meaningful retailers that you could sell an Apple II game through. And then, they’re going to drop a game for no good reason, just because they’re feeling intimidated by this politician that might be able to generate bad publicity?

The politician claimed that our game was going to encourage children to have a disrespectful attitude about the government. [laughs] I mean, it was pretty ridiculous. What was funny about it was, the negative publicity did hurt the sales of the game. What’s sometimes said about publicity is that there’s no such thing as bad publicity. It’s not true. It was bad publicity. It was unfounded. It hurt the sales of the game. It was just a political ploy to get some attention to his own name, and we were all pretty happy when he was eventually voted out of office. [laughs a long time]

Mollie: Speaking of Apple, could the Trip Hawkins of today have stayed at Apple and still be working there, or was it just an inevitable thing that, at some point, you would have left?

Trip: We’re talking about today’s Trip Hawkins if I went back in a time machine?

Mollie: The person you are now versus the person you were when you actually worked at Apple.

Trip: Based on what I know and the maturity and wisdom that I’ve grown into—having now had plenty of years to figure things out—I can absolutely imagine that I could’ve stayed at Apple my whole career. I can also absolutely imagine that I could’ve stayed at Electronic Arts my whole career, and I know that I would’ve done some very interesting things in both of those cases. I’m just a restless kind of guy, so when I was younger and less mature, it was going to be likely that I was going to feel like I needed to change companies or start a new company, in order to service some passionate desire.

Mollie: You were at Apple at such an early point in the company’s life. Did you have any sense of what it could become and what do you feel about Apple as it is now versus how it was then?

Trip: I totally saw the whole thing. You have to realize, before I joined Apple, I wrote and published through a market research firm the first comprehensive and complete study of the personal computing industry—and this is at a time when most people didn’t know what a personal computer was. So, I had a chance to get to know companies in the space, and I had job offers from several of them, and I could tell that Apple was the pick of the litter. So, this was at a point where Apple had only sold a few hundred computers. This is maybe what a lot of people don’t know: The original Apple product was a hobby kit and it was just called “The Apple” and only a couple hundred of those were made. The truly first commercial product was introduced in April 1977 at the first west coast computer fair, and I was there because I was working on this study of the personal computer space and that was the Apple II’s introduction. And I was basically looking for a job in that time frame along with working on the study and basically pretty quickly realized that Apple by far was the most interesting company in the space. Even though they really hadn’t done anything yet. And for what it’s worth, they had some very large competitors. Radio Shack was of course a very large corporation already at that time and had a gigantic lead in terms of how many TRS-80s they had sold, but you could tell just by looking at it that it was a pile of crap. I would never have wanted to have one of those. And I knew I didn’t want to work for a big corporation. I actually did interview with IBM. And I was most interested in the end of their product line, which was the smallest computer and the cheapest computer, but it still cost somewhere between five and fifteen thousand dollars. I think it was closer to fifteen. And it wasn’t really personal. And so I just kind of flirted with interviewing with them, and said to myself that was not where I wanted to go do this. And I also had an offer from Commodore and Commodore was another early leader from the Commodore PET. And they were a much more established company, but they certainly weren’t an enormous company. And then I had offers from other companies, more at the start-up end of things.

When I started at Apple, the company had about 50 employees. Half of those were literally the assembly line putting the Apple IIs together. So, in terms of the office environment, there were only about 25 office workers. Pretty small and so I worked very closely with the founders the whole time I was there, but then four years later when I left, we had 4,000 employees and we were doing about a billion dollars a year in revenue. So, I saw it as a big company, so when you ask me if I knew it was going to be big, the answer is yeah because I was there when it was big. 4,000 people and a billion dollars, that’s big and you also knew that it was only going to get bigger. Most of my time there was spent on identifying the office market, the desktop market as the primary market to develop and that was a change because until I kind of pushed Apple down that path, the common perception in the industry was that the best business use for personal computers was going to be an accounting system for small businesses. Because up until that point in time, pretty much computers used in business were used as accounting systems and they were just used by big companies. Enormous companies had mainframes doing it and then medium sized companies had mini-computers doing it, so now there was going to be small, personal computers and you’re going to be able to have a small business like a mom and pop retail store or a plumber or a this and a that. And of course, when I first arrived at Apple, literally on my second day on the job, the chairman of the board Mike Markkula who was the adult supervision in the company, he said to me “Hey Trip, you know something about business,” which was kind of laughable, but he said that because I had written that study and I had a business degree, and I was always being straddled by a bunch of geeky engineers. Pretty much every other office worker had an engineering degree, even if they were assigned to sales or marketing and it was just the typical sort of Silicon Valley culture of the time. Then I come in and not only am I not an engineer, I have a MBA and one of the slogans at business school was “Don’t ever be the first person at a company to have an MBA,” because everyone else will pull out the knives and use you as proof as to why they don’t need to have an MBA, they’ll make sure you fail. But for what it was worth Apple was like “Hey Trip, go figure out how we can sell these to businesses,” and after I studied that I realized that a plumber is not sophisticated enough to know how to run an accounting system. So that was not going to turn out to be the be all end all.

We didn’t ignore that market. I helped develop that market segment, but I identified office desktops as a far more relevant opportunity. And I didn’t invent the spreadsheet, but I did bring the first spreadsheet apps into Apple and I did identify the fact that’s a linchpin application to build around in the office market along with word processing. And there was a word processor market at that time and they were like $20,000 per workstation and I thought we could really revolutionize this because we can do lots of different applications on the same machine and have it be a much cheaper machine. I built out a product line to do that with the Apple II, but the Apple II was not ideally designed for desktop use. And so we had kind of planned to move it forward with the product thinking that we would start it in the Lisa group and migrate it into the Macintosh group and so all of that was percolating along and it had not yet come to market when I left Apple, but I knew that was going to be a big deal.

Mollie: Do you think it will ever be in Apple’s culture to be a gaming company or a company that really pushes gaming? Because it feels to me that even though gaming has become big on iOS, that Apple still kind of feels like it’s just there and we’ll do some thing to support it, but we don’t really want to get into gaming stuff. And I know that’s partially a Steve Jobs thing, but it also feels like it’s just part of Apple.

Trip: Yeah, I agree with you. I mean, you and I care about games so it’s been a pretty continuous source of sadness that Apple doesn’t love games the way gamers love games. At least now, they embrace it and they support it, so they recognize they have a lot of customers that want to play games, but Apple just doesn’t think like a game company.

Mollie: So say Apple gives you a call out of the blue and says they’re finally going to make Apple TV be a gaming platform and they’re going to make a controller and they want you to go back to them and help them launch it. To head up their game console initiative. Do you go back? Do you do it?

Trip: Well, I’m pretty excited about the job I have right now, but that would certainly be an interesting thing to do if I didn’t have a job.

Mollie: One of the companies you went off to start was Electronic Arts.

Trip: Before I left Apple, I knew for years that I was going to start a game company. In fact, I had made the decision back in 1975 that I would start my game company in 1982, which is exactly what I did. Not too many people were planning that far ahead, but I was thinking pretty far out. Being at Apple was a deliberate part of that strategy, because I felt that I needed to work someplace that is selling computers into homes, and where I can learn how to run my own company someday. I realized that any new company needed to have a big idea, and as 1982 started to get closer, I didn’t yet have the big idea. I was thinking to myself that I needed to have that big idea that I could build a company around, and the more I worked with guys like Bill Atkinson and Larry Tesler and various other, really creative software developers at Apple, I began to realize that these guys were artists. Nobody thinks of engineering as an art form, and yet it is.

So, I really figured that out in the last two years that I was at Apple, and once that big idea kind of took hold in my mind, then it was very easy to flesh out the strategy for the company. Among other things, you’re going to have a diversified portfolio of products, and if you want to have more of your products available in a retail store, you need to have direct relationships with the retailers and expand how much shelf space you have. I decided we would go direct, even at a time when nobody else was doing it in the computer software category. There was no software of any kind where anybody sold direct—they all sold through distributors. And I knew that everybody in Hollywood does it direct and they have more control over their fate and they get broader shelf space and know more about what’s going on at the point of sale with the customers.

So, that’s an example of a strategy that became kind of obvious to me once I had that big idea and another example was if these guys are artists, I need to study how artists are treated in music, moviemaking, and book making and I started reading all these books, biographies, autobiographies, documentary type films and books, to explain how those industries worked and I made some contacts. I was able to obtain a sample of a music recording contract so the EA game developer contract was basically a fusion where I went back to my Silicon Valley lawyer that I always worked with at Apple and said to him we were accustomed to doing software developer agreements, and I had done plenty of those at Apple, and here’s a recording artist agreement and here’s some principals I want followed and I want to create a new contract form that blends these two areas of need together. And then, of course, that contract got ripped off by well over 100 competitors.

There were a number of things that EA did that poured the foundation for the industry and became the standard practices that everybody else copies. The same thing with the record album packaging. That was originally my idea, coming straight out of the big idea that this is a software artist, so why not present their work and have their name on it and have a picture of them and a bio about them like you would if it was a book or music album.

And then it occurred to me that yeah we can have it be like an album and it’ll be very cost effective because obviously if the record industry can afford to do it therefore we can afford to do it. So that led to that album type format that we developed and designed with the printer that was the largest manufacturer of record albums. And I kept track and eventually there were 22 competitors that copied exactly that paper format as we created that new paper format here where this is where you’ll put in the floppy disk and here’s a slot where you can insert the manual and there will be a three-fold deal. But yeah, 22 competitors that just literally copied it.

Mollie: Japan was a huge force in game development at that time, but they were almost the complete opposite, where they made so many of their programmers and developers use nicknames and things like that so that talent couldn’t be poached by other companies. Here you were, pushing those creators to the forefront and directly naming them. Was there ever the fear that a different company might poach some of your team if you push them to the forefront?

Trip: Sure, that was a concern. I think, at the time, we were really confident that we were going to offer the best services, support, and financial opportunity compared to anybody else. We knew we were going to have the best tools, we knew we were going to make financial commitments. Paying cash in advance, for example—nobody else had done cash advancements. It was common in Hollywood, but no one in the games industry had done it. And then, in the end, we knew we were going to offer the most powerful distribution because we were going to invest in going direct and having more shelf space.

Mollie: One of the early EA games I think back to is One-on-One: Dr. J vs. Larry Bird. It was a sports game, but it had a quality that non-sports fans could also enjoy. Was the idea for going in that direction due to technical limitations, was it a design choice, or was it both?

Trip: You have to go back to my childhood, because growing up, the most important heroes to me as a child were professional athletes playing in sports like football, baseball, and basketball. And, playing sports simulation games like Strat-o-matic became my favorite hobby. So, a lot of my motivation to start Electronic Arts had to do with my desire to make computerized simulations of those sports. When I became interested in being a game designer, it was motivated by the fact that I was playing Strat-o-matic Football, and felt that I knew more about football than whoever had designed the game. I thought I could make a better, more authentic football game than this. And I was a big football player at the time and had read a lot of books about football and coaching and strategy and play design so it was a very deep hobby and interest. So that was the first game that I ever published, it was a board game football game that I designed with cards and charts and dice. It was kind of in the same tradition of games like D&D and Strat-o-matic, it was that type of game. And that’s when I realized this is a hell of a lot of fun and I really like doing this and of course it didn’t do well financially because I was a teenager and didn’t know how to run a business and that’s when I realized that I was going to do it again, but it’d be computer games and I’m going to wait until I know a lot more about business before I do it.

And then’s when you get to the next decade of planning that gets to the foundation of Electronic Arts. So, by the time Electronic Arts gets founded, of course, as soon as I have a company, I’m going to be figuring out how to get the sports games made because those are the games I want to play. And it wasn’t really practical to take the first step by doing a really ambitious team sport. So when you look at the first games that we did, the very first game was the Dr. J vs. Larry Bird game and the next game that followed that was World Tour Golf and if you think about those games, basically you’re making a golf game and I’m going to have a flat golf course with a couple of different colors to differentiate grass and sand and I’m going to have to animate one golf swing, so that won’t be terribly demanding. And then with Dr. J vs. Larry Bird I only had two basketball players to animate and I had as a child seen these Vitalis commercials on TV that had done the Home Run Derby that doubled as an advertisement. Actually I don’t think I saw them as a kid, they might have preceded me and aired sometime in the 50’s, but the Home Run Derby was invented as a way of promoting some product on television and then by the 60’s Vitalis, this hair cream company did it, and I decided that we would do something like that but we’ll do it with basketball players doing a short game of one-on-one and we could edit it into a short 1-minute TV commercial. I just kind of instinctually recognized from my time with Apple II to not try to animate too many characters, let’s do something simpler as a starting point.

Since I was actually more of a football fan, I figured first how about a simpler football game that is basically a quarterback throwing passes to a receiver and how about I bring Joe Montana and Dwight Clark into that because the 49ers had just won the Super Bowl and they were the local team and suddenly had a national reputation and that was really the first idea that I had and then I found out that Montana had a promotional relationship with Atari. He wasn’t used in any software or appeared in any games, he was just a spokesperson to sell the Atari hardware product line, but that blew that out of the water. So, I thought about it and I wasn’t sure then if the game idea worked because it wasn’t real football and I couldn’t have Montana, so then I went to basketball. And I personally was a huge fan of Julius Irving, Dr. J, and I knew he had this great rivalry with Larry Bird and they’re both very different kinds of players. They’re both great, but one is a classic guy who penetrates and is dramatic around the hoop and the other was a well known outside shooter. And there was an intense rivalry between their teams on top of everything else, so there was great drama and story between these two guys. And when I was playing Strat-o-matic or even the football game I had created, it meant a great deal to me to play with the real players. So, always for me it was about the authentic experience. And with the basketball game idea I figured I wanted these real players to be in the game. Up until that point in time, nobody had brought in an expert, of any kind, to help design a video game or appear in a video game as themselves. It just had not been done. So, Dr. J was the first such person to sign a contract to do it and we were able to get a hold of his agent through a local lawyer that we knew that knew the agent and he was able to convince [Dr. J] to consider it and one of the arguments that I made to Julius was that he was going to be retiring within a few years and this would be a way for him to extend his brand and to continue to be an ambassador for basketball. And this was the medium that his kids were going to grow up on and these are the kinds of things his kids would love to see him doing. So those were the arguments that appealed to him and got him on board and, of course, one we got him on board, you just have his agent tell Larry Bird’s agent to do it. And you can say the rest is history.

Basically, I kind of pulled everything together about this. It was my idea, I put the team together, I was the Executive Producer throughout the project, basically it was my game design down to nitty-gritty details like you could shatter the backboard glass and have a janitor come out and sweep it up. I was inspired to do that because Darryl Dawkins had become well known for shattering backboards and so I figured we could have a little fun with this idea. But even the little details, I learned a lot about user experience back when I was at Apple and helped pioneer that field and I was always in the room whenever we made these really epic decisions about how human beings were going to use computers. In fact, it was a friend of mine at my request who brought the first mouse into the company. So, again, I was in at the ground floor of all that and became a pretty good expert at user-interface and user-interface design and so I understood the difference between pressing down on a button and lifting up and releasing the button. Those are actually two different actions and you can say you just hit the button, or you could say to hold the button, because then we’ll do a second thing depending on the release of the button. So, in Dr. J vs. Larry Bird the things that I worked out and lined up with basketball is that the correct technique when shooting a jump shot in basketball is you’re supposed to release the ball at the height of the jump. So that’s in that game because I said your shooting is optimized if there are no defender hands in your face and you release the ball at the height of the jump. So if the shot is uncontested and you time the release of the button perfectly that’s your greatest chance of making the shot.

Meanwhile, you can actually release the button on your way up, or on your way down and that led to one of the more fun things you could do in the game, which was be way outside the 3-point range and you could jump up in the air like you’re going to do a jump shot, but then wait until you’re coming back down and your feet almost back on the ground and then you release the ball so now you’re back on the ground just as the ball is releasing from your hand and you can run to the basket and get there about the same time as the ball is hitting the rim and you could basically alley-oop yourself. That’s still one of my favorite things to do in any video game, to lure the defender out and make it look like I’m doing this 3-pointer and then come back down, run around the guy, beat him to the hoop, and then do a slam dunk off my own rebound. Anyway, you can imagine by the way I’m talking about it how fun it was to design that and why I still think of it as one of the best game designs because of the elegant simplicity of it. Because there really wasn’t much you had to do. In fact, it’s one of the few games where in the entire history of Electronic Arts, even to this day, the retailers that buy the games almost never play the games. And even if you go out to show them the games, because I’ve made loads of sales calls with retailers and shown them video games that I want them to order lots of copies of and you’ll be showing them a game and say “Here, you try” and pretty much the only game where you could actually get them to try it and where they would light up with joy because no matter what they did they felt successful at it, was Dr. J vs. Larry Bird. Because, basically, no matter what you did with the joystick, the guy runs around in some correct part of the court, it may be incoherent but, you couldn’t run out of bounds, you couldn’t do it wrong, and then if you hit the button the ball was flying towards the hoop. And it didn’t matter exactly how you timed it, you felt good because you took a shot.

Mollie: Have we lost some of that elegant simplicity in gaming? Can you still have as much fun developing games today given how much you need in terms of programming and art assets and audio assets and staff and things like that?

Trip: Oh, absolutely, and I think one of the things about mobile devices and the Internet is that it’s a more mainstream market. You have billions of people playing games now and a lot of them are casual gamers. As a result, if you’re designing for a casual gamer who is also, no doubt, a social gamer, you don’t have to build Grand Theft Auto. You don’t have to build something with the depth and sophistication of Madden. And there are plenty of good games, Angry Birds comes to mind, that have 2D graphics and that didn’t require enormous budgets, they just required a sense of humor and good, clean design. I think there’s more and more opportunity like that all the time because there are so many devices and so many access points. And certain things have gotten a lot simpler. So you no longer have to build a company to get a product into distribution. You can basically just have a link in the cloud and people can get to your game and they can try it for free. So, it easier for an unknown developer to come out of nowhere and make something that turns out to be the next Angry Birds. It’s a somewhat misleading proposition in that a lot of people get caught up thinking that the odds of that are good. “Of course I’ll make the next Angry Birds.” Actually the odds of that are probably closer to 1 in 100,000. Obviously a lot of creative people get disappointed but I think if you think about the creative spirit and it’s true for musicians, writers, and people who make games, they are so enjoying the process and they’re so passionate about the creation that in the end the journey is worthwhile, even if you don’t have the commercial success. And I’m sure other people in the industry feel the way I do. I love my failures just as much as I love my successes because I know what I was trying to create and I what was good in that creation. So, you go back to a game like M.U.L.E. that I was very intimately involved in helping create. I can’t say that I’m the creator, but I was one of the lieutenants assisting with the creation.

And, to this day, I think that’s one of the most remarkable games made by the industry. And Danny Bunten [now known as Danielle Bunten] is partly in the Hall of Fame because of that game, but it was a commercial flop. People still talk about it. It’s got an enormous cult following, but it was a flop. It was just kind of ironic, because they made another game, The Seven Cities of Gold, that was much more of a commercial success. I love that game too, but I’m much fonder of M.U.L.E. And to this day, I’m fond of other games, you know, like the Army Men brand. I’m still fond of it. It got a lot of ridicule from other people in the industry who didn’t yet understand what it meant to make a casual or a game that had a sense of humor. They were trying to basically compare it to hardcore games, and that was not really a fair comparison.

But yeah, at some point, as a creative person, you separate your point of view from the critics and you separate it from what happens commercially with the public and you take whatever public success you have with a grain of salt.

Mollie: EA starts working with sports figures, and at some point, John Madden comes in for football. What was it like working with him, and is there any truth to the idea that he wasn’t willing to put his name on the game if there weren’t 11 players on each side?

Trip: First of all, John Madden is a great entertainer. If you hang out with him personally, every third word is the F-word. The fact that he’s never said that on the air tells you what a consummate professional he is. So, you’re dealing with a very professional entertainer, and he’s enjoyed cultivating the mythology of the story you just mentioned.

The truth of the matter is that, in order to bring John on board, he made me fly into New York City, meet with his agent, and convince his agent that he had to make the deal. We made the deal, and at that point I had not met John—I had only met the agent. We made the first payments associated with the deal, and then we made arrangements to have a meeting. I had written an enormous design document, probably about 80-pages, that was, in fact, a design document for an 11-on-11 football game. The first thing I needed to do was take him through the document. I had a ton of questions for him to clarify. Am I doing this right? Here’s a detailed question about how, say, bump and run coverage works or how a linebacker reading a run versus a pass, what are they doing. I had stored up a whole bunch of questions I needed to ask him because I was then going to go on to design how the computer did AI and how the computer chose plays and how the computer would choose which personnel to put on the field, which formations to run, how to set up a play by… Just every little detail. What am I going to do based on down and distance, time in game, score? There was a lot that had to be done. I knew I had this two-day period with him, so I had to go through that, and that was going to be the first thing. One of the questions I had was just a little bit of a risk management thing. Since I had played football, I was familiar with skeleton. Skeleton is something you do in football practice where you don’t need the guards and the tackles, because you’re not doing running plays. In skeleton, you’re basically practicing passing plays, so there’s seven guys on offense, which includes the passing play and all of the eligible receivers, and the center, who’s going to snap the ball. And then on the defensive side, you would have, again, everyone except the defensive ends and the defensive tackles. You’d have the other seven guys, all the linebackers and the defensive backs. There was still a little bit of a pass rush, because the linebackers could come in, and your receivers were all running pass patterns and you were throwing the ball. Of course, this is a real thing that comes from real football. One of my questions was, hey, maybe in one of our practice modes, we’ll offer skeleton as a practice mode so that when you’re drawing up your own plays in the play editor, you can then basically practice them with the skeleton method like you do in real life. At any rate, I still had some question marks about how well we would be able to animate 22 players on an Apple II, which was our first hardware platform. So I did, in fact, take him through this question about, hey, what about skeleton? Should we have that as a practice feature? And then I did just ask him this one question, which was, hey, what do you think about if we have trouble animating 22 players, what do you think about the idea of, as our fallback, just having it be seven on seven. He then had sort of a one-liner, said, Well, that wouldn’t be real football. I nodded my head and said, Yeah, you’re right. That’s not real football. And then we moved on.

So it wasn’t really that we couldn’t do it. It wasn’t that I wanted to do it. It was just one of these risk management questions, and it was among literally hundreds and hundreds of other questions that he was being asked while I’m kind of clarifying my thinking. I’ll tell you right now, if in the end, we couldn’t animate 22 guys and we’d decided to make it seven on seven, he would’ve still been on board. Now, by the way, it took longer to make the game than any of us expected, and he and his agent both got pretty upset about it, because there were some progress payments that we ended up delaying. That they really got upset about. There was one point in one of our follow-up design meetings where we were talking about something and something being correct or not correct. I think there was a play formation where the developer had kind of carelessly had a halfback that lined up behind a guard, which never happens in football. They always line up either behind the center or behind the tackle, and he got upset when he saw that. Then the F-word was every other word. There was one point in a conversation where he did, in fact, express—for like maybe 30 seconds—he said, You know, I do have to be a little careful about what you guys do to make sure I protect my reputation. I’ll tell you right now, there’s a notable difference, and right now I’m working with experts right now that are master teachers of social and emotional learning, which is known as SEL. And they’re extremely worried about their reputation. They don’t care about money. They really care about their reputation and the academic and teaching community. So it’s kind of funny, because I work with this one expert where she’s known me for more than 15 years because the way I learned about SEL was my children went to one of the schools that was at the foundation of it, and so I started hearing about it through what my children were doing in that school, and she taught in that school for like 30 years. So when I got the idea to do this thing, I was like, Yeah, I want to work with her, because I know she’s like the world’s leading authority on this. And, in fact, that school was the featured school in the famous book by the New York Times science writer Daniel Goleman that came out twenty years ago called Emotional Intelligence [full title: Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ]. The school my kids went to was the featured school. Anyway, to make a long story short, it took me six months to convince her to help me make this game that we’re making today, the game IF…, because of her concern about reputation. It was never a concern about money. Never. Now, on the other hand, I compare that to all of the contract negotiations with athletes and coaches, it was always about the money. It was never about the reputation. [laughs] Indeed, that Jerry Maguire movie line, “Show me the money,” it’s pretty valid. It’s actually one of the things I really respect about John Madden, that he had faith in us. I think right from the beginning he could tell that we were as serious about football as he was, and that we wanted to do it right. Again, this has just always been, for me, the really essential thing about my experience as a gamer, is that I wanted it to be authentic. And that’s why I was willing to work on it for years to get it right. And by the way, I’m taking exactly the same approach with what I’m doing now.

Mollie: Obviously you’re not at EA, and you’re not working on Madden anymore, but do you miss the days when John Madden was on the cover, or do you think going the cover athlete route was the right direction for the series?

Trip: I think they’ve had a lot fun with athletes on the covers—it’s become a cultural thing. Athletes are really thrilled when they get chosen, and they love to trash talk each other about it, whether they’re chosen or not. We had that going on with High Heat Baseball back at 3DO. Although, I think John Madden as a brand name could be a bigger and broader brand today than just a football simulation game. I think that was a lost opportunity. You look at how huge fantasy sports is, and I cannot think of a better human being than John Madden to be the brand name for fantasy sports. That’s just something that was never pursued or considered. I think it’s an example of how product disruption works. The Internet came along and the game industry did not understand it. Even something like fantasy sports came along and the game industry did not understand it. Fantasy sports is an extremely enormous industry, but it’s not really an industry that the traditional game industry participates in. And yet fantasy sports are the most scaled example of what I think a modern videogame will be, which is a cloud-based game service that’s available, that can be accessed from every screen size and every device and you’re always able to kind of pick up where you left off and you’re always able to communicate social, and it’s truly interoperable cross-platform. Of course, the reason it’s that way is with fantasy sports you’re generally just checking into a website. You’re trying to find out, did my guy hit a home run or not. Hey, there aren’t that many video games that have audiences as large as fantasy sports.

Mollie: Another thing that stands out about EA, for me, is the era of your Genesis releases. Your clamshells were different, your cartridges were different—it was almost like you guys were like this rogue company that was saying, “Well, we’re going to do things our own way, and we don’t care what anyone else thinks, and we’re going to have our own cartridges and our own cases and everything.”

Trip: We absolutely were rogue. I didn’t like the Nintendo licensing program—I thought it was draconian, confining, and extremely un-American, and that’s pretty much how all the other American game companies felt. That’s why none of us supported the 8-bit Nintendo when it came to the U.S., and basically why the American game industry hoped that it would fail.

There was only one exception—one America startup, Acclaim. Pretty much the rest of America was thinking, “Man, we don’t like this business model, I hope this doesn’t fly.” [laughs] Needless to say, everybody was kind of left flat-footed when it succeeded, and as it did, it started to kill off the market for, say, Commodore 64 or IBM PC games. Everybody was scratching their heads and wondering, “What the heck are we going to do about it?” As I started thinking about that, I said, “Well, we’ve kind of missed the 8-bit boat, but there’s going to be 16-bit.” We’d made all these great games on the Amiga, we put them on the ST, the 16-bit Mac, the 16-bit PC. We’d even ported 16-bit coin-op cabinet games like Marble Madness from higher-powered 16-bit cabinet games into the consumer market. We had tons and tons of 16-bit experience, particularly with the Motorola MC6800 processor.

So, when I heard that Sega was planning to introduce a 16-bit machine based on the 6800 processor, I thought, “Oh! Well, that’s a different kettle of fish.” Sega had 1-percent market share in 8-bit, and they had no third-party program. I was thinking, “Oh, you know what? I bet Sega’s going to come in, and they’re going to have a good 16-bit product before anybody else. But you know what? Either they’re not going to have a third-party program, or they’re just going to copy Nintendo’s, and that’s not good. All right, we’ll reverse-engineer it, and we’ll do our own thing.” At that point, we’re going rogue, and we’re preparing for the fact that, yeah, these guys are probably going to sue us, claiming that we’ve infringed on the copyrights.

But what happened is that, after spending about a year and a half reverse-engineering the Genesis and developing products and planning to come to market without a license, at the 11th hour, I thought, “You know, I’ve got to at least go tell Sega what we’re doing and see if we can make peace. I’m sure as heck not going to do a Nintendo-type license with them,” but I basically went to them just before the CES show in 1990 and said, “Here’s what we’re doing. We’re going to announce it at CES, it’s perfectly legal, we did a clean room, you’d be wasting your time if you decided to sue us, we can basically publish games without needing a license from you, and we’re not infringing on any of your intellectual-property rights. But, by the way, we’d be happy to consider being partners with you in building up this 16-bit market.”

I’ll tell you why we went public at the time we did [in 1989], because this’ll make you laugh: We’d been profitable every quarter for five years. We didn’t really need the cash from going public. In fact, we only netted $8 million from the public offering. But I wanted to go public and get the $8 million so that I had a little bit of a cash war chest for the likely Sega lawsuit. I was prepared to fight it; I didn’t have a problem fighting to prove that it was OK for us to do what we’d done. But we ended up making peace, and it turned out that I was able to get a really good deal partly because they were pretty convinced that I was going to do it anyway, and that they couldn’t stop me.

Mollie: You then went from reverse-engineering someone else’s console to making your own, the 3DO. Was 3DO a case of a right idea at the wrong time, or do you think the path you went down just wouldn’t have worked out?

Trip: It’s a really interesting “what if” case, because when you look at it in hindsight, it looks like it was a complete waste of time. When you see the success of the Sony PlayStation a couple years after 3DO, you think, and see, that there was no need for 3DO because Sony’s PlayStation was going to do everything that we set out to do. The funny thing about what actually happened is that Sony, in fact, almost joined forces with 3DO, and Sony copied a lot of the things 3DO was doing. I’ve had Sony executives tell me that. So, it’s just kind of ironic. I think the problem with 3DO is that there were a lot of the right ideas, but the timing wasn’t quite right. There were a couple of fundamental flaws in the approach that was taken. I think 3DO was a trailblazer, and it was a consciousness-raising event that helped the industry and the public figure out that there was some benefit to multimedia technology and that there was a future for things like digital video and the Internet and 3D graphics and the use of optical disc storage and even elements of social and casual games.

Mollie: So when you see Microsoft unveiling the Xbox One, and they’re talking about gaming and multimedia and all these things together, are you sitting there thinking, “I did that! I did that years and years ago!”?

Trip: My ego doesn’t need to go there; I think that would be kind of silly. Until something’s commercial successful, there are probably a lot of people that have ideas in their head that maybe don’t get very far, but maybe they get further but they’re not commercially successful. You have to give credit, in the end, to the things that genuinely get scale.

Mollie: 3DO often gets quoted as the most expensive console of all time when, to be fair, from memory, its retail price was $599, and the Neo Geo actually came out retail at $649. Will you at least say you got a raw deal in that regard?

Trip: Yeah, and I have to say, I appreciate you remembering what you just said correctly, because there are so many people that think that 3DO cost $700, and virtually nobody ever paid that. The way Panasonic operated at that time, as a consumer-electronics manufacturer, they’d establish a list price for something, and it was fairly common practice that they would fatten up that number and then tell the dealer what a fabulous discount they were giving him, and everybody—wink, wink, nod, nod—would know that the retailer was going to be able to then profitably sell it at a lower price.

From day one, the street price was $599. There have been plenty of other game platforms that have been more expensive. When I started at Apple, the Apple II had 4,000 bytes of RAM, no storage, no display, no nothing, and that thing cost $2,000. You didn’t get a whole lot for $2,000. In fact, the first DVD players cost $1,000. It just didn’t seem like it was that crazy if there was a reasonable value proposition to think that we could make a higher price point. But that was wrong. That was a mistake.

Mollie: One of the things that was most interesting for the 3DO was that, up until that point on the console side, you had a company who made a console. You had a Nintendo platform, a Sega platform, whatever. But the 3DO idea was that you could have these different companies making their own versions of the 3DO. You could have the Samsung version or the Panasonic version or whatever. It’s an idea that kind of came out and went with the 3DO, but it seems like we’re getting back to that with the Steam Box and what Valve is trying to do with it. Having gone through that with the 3DO, do you think that idea can work or is there a strength in having one company, one piece of hardware, one organization pushing it?

Trip: Obviously, in most of media history—and you’re seeing this today with Android tablets and smartphones—a model where there’s a standard that’s supported by a group of manufacturers is more likely to be successful, and there’s a variety of reasons why it will be more successful. Generally, when it doesn’t work out that way, there’s usually been a really good reason for it. I think in Apple’s case, Apple got to be so good at user experience that they were able to benefit from having complete control over the experience. In the case of video games, because it’s a razor blade model, you kind of have to have a brave lead manufacturer, as you saw with Sony and the PlayStation, where they were willing to lose money on the hardware. Sony basically put down a $2 billion bet. They invested $2 billion to start the PlayStation business, and that included fab facilities for custom chips and being willing to lose money on the manufacturing costs of CD players and memory and everything else. I remember when Sony came to the US and it was at the June CES. And this would probably have been ’94. So, June of 1994, and there’s a panel… Wow, what was his name. The Caucasian guy who was head of Sony PlayStation US at this time. [It was actually E3 ’95 (Sony Computer Entertainment America didn’t even exist in ’94). The man’s name was Steve Race, formerly of Atari.] He announces that it’s going to be $299, and I think pretty much everybody in the room gasped, because everybody was assuming it was going to be $399. And then Howard Lincoln was on the stage and said, “Well, I hope Sony shareholders like that.” Or, it was something like, “I don’t know how Sony shareholders are going to feel about that.” It was such a money-losing proposition. Literally, Howard Lincoln was mocking it. And, of course, the irony is that by January— Obviously, it’s not going to kill them financially for Christmas of ’94 because quantities are limited. Back in those days, if you could build and ship a million hardware units for your first Christmas season you did pretty well. But in January of 1995, the price of RAM plummeted. That was one of the things that made $299 such a risky choice for them, is that RAM was really expensive in the early 1990s because of growth in the PC market, and it was sucking up all of the supply of these computer chips. And it takes a while for the semiconductor industry to build new factories to catch up with demand, and they finally caught up by the end of 1994 and they had excess manufacturing capacity and they wanted to use it and get rid of their memory chips, so there was a dramatic reduction in the cost of RAM. Sony had 3 megabytes of RAM in a PlayStation, and basically the semiconductor industry said, “Hey, we’re going to give you this enormous refund. We’re going to make you look smarter for saying $299.” Sony, obviously, they manufactured chips as well and maybe they could see it coming and maybe they knew they wouldn’t have to get burned for too long at $299.

Mollie: I remember for years reading magazines like EGM, Game Fan, and Next Generation, and reading about the M2. The M2 is going to be the follow-up to the 3DO. It’s going to be this super-powerful system. It’s going to be an add-on. It’s going to be its own system. There’s mock-ups and everything. Looking back on it now, do you think there would have been a place for the M2 at that point, or is it maybe better that it didn’t end up seeing the light of day?

Trip: Oh, there was a place for it—the problem was in terms of learning curve. Again, you have to give Sony credit, because at a corporate level, they had been very active in the music business for more than a decade because of their joint venture with CBS Music in Japan. They had developed a pretty decent understanding of software and the dynamics between software and hardware compared to other hardware manufacturers. Plus, they’re Japanese, and they had a front-row seat watching what Nintendo had been doing. You might recall that there were a few time periods where Sony and Nintendo snuggled up to each other and tried to figure out how to be partners, and it never worked out, because you couldn’t have two kings.

Sony had really done their homework, and they had really been paying attention, and they were much more culturally open to embracing the kind of needs and issues you have if you’re going to be involved in software. For a company that had a hardware history, they executed really well in entering the game business and addressing a lot of the needs and issues on the software side of the equation. Frankly, Matsushita—which was a better hardware company than Sony, and had beaten Sony on the VCR and would later beat them again on DVD—really never got a feel for software or a feel for games. It was somewhat antithetical and difficult for Matsushita to get into the kinda thinking that was required. And, it was a little disjointed, because I had assumed that we would be able to achieve higher hardware prices. I was not convicted that we had to use the razor blade model, where the hardware had to lose money and there had to be software license fees that would repatriate that money. 3DO started out with a much lower license fee, believing that we could get that to work, and we didn’t really have the ability to then offer a hardware company essentially a kickback on software that would’ve allowed them to lose money on hardware.

Obviously, in hindsight, that just didn’t work at that particular point in time. But I think if you look at it now, people are happy to pay whatever they have to pay for their next iPhone, and they’re not paying really high prices for software because there’s a big license fee tacked onto it. For whatever reason, there was a period of a couple decades where video games had to be on the razor blade model. It wasn’t true with media before that, and it’s not true about media now, but during that time period, that’s the way the public operated—and the public would not pay to buy a videogame console above a certain price point. But they would pay $50 or $60 per game—go figure. Good luck trying to get them to do that now.

Mollie: That kind of thinking seems to lead into what you were doing with Digital Chocolate, and there were some people who were kind of like, “Why is someone like Trip Hawkins going to mobile gaming? Why is he lowering himself to those kind of levels?” Did you take any of that personally? Do you think that our industry still has a problem really giving proper credit to the mobile gaming space?

Trip: Well, I think everybody respects mobile games now. Companies like Jamdat are kind of a distant memory, and there was a whole battleground around feature phones that Digital Chocolate came into kind of late. Since the channels of distribution were controlled by the telecom companies, it never really went anywhere, because those companies didn’t really understand media and didn’t know how to develop media merchandising and promotion. Obviously, they didn’t have much feel for the device experience, either. It was frustrating, because despite the network being poor in terms of performance, and the devices being pretty limited, companies like Docomo had in fact built a huge successful business with feature phones in Japan—including the fact that they invented the idea of the app store and microtransactions and virtual good for mobile and social features in mobile. Then, there was also their enlightened thinking about the value chain and the supply chain and recognizing that, hey, we’ll only take 10% of the money, we’re going to make a lot of money on data plans. We only need 10% as a fee for doing billing and settlement on the phone content that gets purchased.

So, basically, Docomo created an enormously successful model before anybody else. The Koreans copied it, so it became a big deal there. What got built in Japan and Korea, eventually that understanding radiated out to other markets, and when then pushed further by Apple and their disruptive intervention—not only around the device experience, but shifting the distribution model outside of the telecoms and into the App Store.

But, you know, it was unfortunate for Digital Chocolate, because the company started too late to be Jamdat. When the whole Docomo thing didn’t spread beyond Japan and Korea, there was a limited opportunity with feature phones, and yet we made that work anyway—and it became a profitable company. As a result, by the time the iPhone and Facebook came along, we were trying to grow and protect a profitable business. You don’t spend years to get to a profitable business to then just throw it away overnight for a few magic beans like Jack and the Beanstalk. So, we could look at these emerging new phenomena like Facebook and iPhone and say, well, OK, we’ve got this big successful product line, these award-winning mobile games—you know, let’s bring them over to the iPhone, but we couldn’t make the same kind of disruptive commitment as a new company like Zynga. And, as a result, we missed that wave too.

So, Digital Chocolate kind of got caught in between. We proceeded to make a bunch of successful pivots and we became a successful Facebook publisher—just in time for Facebook to drain all the water out of the bathtub. It was a frustrating experience. And, of course, I think the biggest challenge in the industry in the last five years—as it’s gone to free-to-play—is figuring out how to get the discipline of game design to do a more effective job at causing virtual goods economies to be vibrant enough that they monetize well. Unfortunately, the game industry right now is kind of one-dimensional, because there’s this expectation that everything should be free, but then there are very few games that monetize well, and then only those games can buy traffic and do marketing. And so you end up with all the revenue going to a handful of games that are at the very top of the chart like Candy Crush Saga, and it seems a little arbitrary and it’s not really scalable. You’re only ever going to have a few games on the screen of your phone at a time, and they’re going to be the ones who are at the top of the free chart.

And companies are paying a big price to get there—they can only stay there if they happen to have a game that monetizes well. You know, obviously there are developers that had to have several shots at this before they finally figured out how to get one right, and in some cases those companies don’t even ever get a second one right, so in some cases it turns out it’s kind of like a hit song—a one-hit wonder band. But that was my biggest disappointment with Digital Chocolate, was that we figured out everything else, but we didn’t crack the code on monetization. And a lot of the same people left Digital Chocolate, went somewhere else, and eventually figured it out. We just didn’t have enough time.

Mollie: On the other side of things, instead of looking back, what gets you excited about games these days? What fills you with hope about gaming?

Trip: I’m really excited about the time being right to bring what we know about games and technology into the field of education. There’s this polarization now, where what goes on in the classroom is a big challenge, because [too many] Americans that enter the public school system fail to graduate from high school. That’s a disaster, considering how much money we spend on it and how much we care about it. And then, on top of that, we have these issues with school climate, where so many kids feel bullied or cyber-bullied, and we have school shootings, youth suicide, and just a lot of challenges with kids coping in these particularly large, urban public schools.

I think that there’s a legitimate crisis where the game industry can actually help deal with all of these issues, and what it boils down to is recognizing that and learning that you need to meet people where they’re at. Learning has to start with getting someone’s attention and having them be motivated. If nothing else, that’s something the game industry knows really, really well. Children’s attention today is going to video games, and they’re motivated to perform well in the game. If that’s where their attention is, that’s where learning has to go.

Mollie: The long-standing thought is that games can either be fun, or they can be educational—it’s exceptionally tough to make them both.

Trip: Well, the reason it’s worked out that way is that most of the game industry is young men who want to make games that they want to play. They don’t really know very much about kids, because they’ve not yet been a parent, and they don’t know much about girls, or women in particular. They don’t understand mothers or teachers.

Mollie: So that was the motivation for starting your new company, If You Can, and its first game, IF…

Trip: Right. In fact, this is the whole company. It’s called “If” after the Kippling poem, the poem that start out, “If you can keep your head when all about you…”

What I like about what we’re doing is that it’s on the softer side of academics—it’s not hard science, it’s not math. It’s about social science. It’s basically characters in a story that you care about that have classic human situations and relationship situations and conversations and choices that they’re making in the game, and we can use that as a platform to teach all kinds of social science. The focus for us, right now, is teaching this emerging curriculum that’s become known as SEL—Social and Emotional Learning—and this is something that kind of burst into prominence after the publication of the famous bestseller Emotional Intelligence. After that book came out, it galvanized that community and research that first was able to prove that the schools that were starting to teach SEL, the pioneers in it, had research evidence that school climate improved, that discipline problems reduced, that bullying reduced, that student function and well-being that that got better, that incidents of depression was reduced. So there’s a lot of research findings around the climate and the well-being of a student, and then following that, a bunch of additional research learning that schools that were teaching SEL, the kids had higher academic achievement scores in subjects like math and English, that are part of common core.

This is all really good support for the benefit of this kind of teaching, and so it started to get more government attention and it’s only been in recent years that the first government teaching standards have come out for SEL, and it’s pretty much like you would expect in a subject like math, where the teaching standards will say what they want a first grader in September to know about math, and when it is later on that they’re supposed to know everything about algebra or everything about calculus. And curriculum is spread out over a continuum of several years, and the assessment of it and the testing of it has to confirm what’s supposed to be known at different times, right? So these teaching standards have begun now to emerge from the government for SEL, and just in the last couple of years the government has started putting muscle behind it, starting to fund it and starting to make policy decisions to support it. And a lot of it has happened just in the last couple of years. So it was kind of a crescendo, where it feels like the time is right, and there’s a very critical need for it, so we’re excited because we have figured out how to do those three things successfully in a game that pre-teen children that are school children, between the ages of six and 12—so these are kids that have left home and started school, that are dealing with school climate, that are learning to read, and eventually are moving into middle school and high school, so it’s a fairly critical developmental period in terms of their social and emotional skills—and we’ve come up with a very good formula, again following the same kind of methods as I did with EA Sports of bringing in experts and using government standards and going according to the rulebook of how it needs to work, and we’ve wrapped that into a very clever videogame design that’s got a great story and great characters and fun gameplay.

Mollie: Why does it matter if games teach us something?

Trip: I think it’ll be a big letdown if the medium of games only ended up being used for entertainment. It just fails to exploit its inherent potential. When I was a kid, I kind of discovered on my own that I was more mentally engaged playing board games than when I was watching TV, so I figured out that this was better for me than that. Obviously, a lot of games kind of dumb that down. What I noticed as a child was, hey, if you’re simulating something real, that involves real human situations, either real or fantasy, you know like with D&D, they’re pretty real human situations, but yeah you’ve got magic and dragons, which makes it more fun. You could just tell that you’re learning stuff that’s more potent, that can be applied to real relationships in real life. Same thing if you’re playing a flight simulator or, you know, learning how to be an NFL football player or call NFL plays. So it can be done, and it should be done. There’s a crying need for it.

School systems, you know the didactic learning model that’s been around for about 500 years, it had a good run. [laughs] It had a good run. But the idea that everyone is paying attention to what the teacher is saying in the classroom, or doing a lot of supplemental reading at home, it’s not happening. A lot of money’s being spent and going to waste, and almost half of American children that enter the public school system don’t even graduate from high school. I mean, that’s a pretty serious problem. Of course, we’re focused on social and emotional learning, because there’s now also psychological issues that kids have, because they’re not learning this stuff by the means they would have used a couple hundred years ago in a tribe or a village, where they’re growing up alongside your parents and their modeling, and you’re going to religious services. It’s just kind of fallen in a crack. I didn’t learn anything when I was growing up about how to manage my emotions. In fact, my father was setting a really bad example about that, and you’re just kind of picking up his bad habits. So, this is really necessary stuff, and school climate has become a big issue with bullying, cyber bullying, youth suicide, school shootings—it’s a real crisis.

Mollie: Will people say that Trip Hawkins had a “good run” when the end of your career comes? How do you think you’ll be remembered, and what do you hope you’re remembered for?

Trip: [laughs] That’s a good question. I think the thing I’m best known for is being the founder of Electronic Arts, and I’m happy for that, because EA is like one of my children. It’s important, to me, to have people remember that I did that. The other thing I think that I am known for is that I did innovate a lot of business practices, and practices around how to do game development and how to manage game development. What is more precious to me, personally, is what I did creatively. Personally, I would rather be remembered for what I did as a designer. That includes the very central role that I played on the EA Sports games, and later High Heat Baseball, but also what I’m doing now with IF… and what I did early at EA with games that had educational value like Mule. Again, this is maybe something you don’t know about Mule, but at my direction, we had the game bottle several critical economic principles that were straight out of a first year of college economics, and it meant a lot to me that we had a game that legitimately simulated these economic principles. And, in fact, I wrote the manual for the game. Because, of course, everybody knew that I had to write the manual because I was the only one who could describe the stuff. [laughs]

Mollie: So, from here, I’d like to ask you some more light-hearted questions. To start, what Dungeons & Dragons class is Trip Hawkins in real life?

Trip: I might be a Paladin. I’ve played a Paladin before, and that’s fun. But I also notice that it’s fun to be a Thief, and it’s fun to be chaotic. [laughs] Those are somehow characteristics that I think I can relate to.

Mollie: If you were to show up in one of the Steve Jobs bio films, who would play you?

Trip: Boy, that’s a good one. You know, there’s an actor that I’ve always related to really well who’s similar to me in age. I adore some of his movies—particularly his baseball movies Bull Durham and Field of Dreams—and that’s Kevin Costner. I think I’d enjoy watching him play me. Of course, if you’re talking about going back to when I was much younger, then it’s a tougher question. [laughs]

Mollie: If you had some free time and were allowed to do nothing with it but play a videogame, would you go back to a classic title that you’ve played before or something new that shows what gaming is today?

Trip: You know, for me, it’s never been about the degree of high performance or production values. The games I’ve always liked the best are the ones that I can play with other people, so they’re social. For that reason, they often need to be more casual, so you can make it more accessible to more people—including, say, your own children. I always look for classic gameplay, in my mind, that’s simulating something interesting or that has a little bit of humor value to it.

I’m thinking back on simple games like One on One: Dr. J vs. Larry Bird or a game like M.U.L.E. or Return Fire—that was one of my favorite games on the 3DO platform. And, of course, my personal favorite sports game ended up being High Heat Baseball 2000. I worked on that for a number of years and got a lot of gritty details into it that made it a lot of fun to play it, because it was so much like the real thing.

Mollie: On the flip side, what favorite board/card/tabletop games do you have these days?

Trip: There’s a game called Munchkin that’s a parody of D&D, and I love to play that with my 9-year-old son. There’s another, a parody of war games called Snit’s Revenge. It’s a really old, funny game with a great sense of humor—again, I tend to like games that have a sense of humor. Another one that’s a family favorite is called Fist of Dragonstones. I think I have a collection of well over 1,000 board games, so there’s a lot to pick from.

Mollie: Are you surprised or not surprised that board games have maintained their popularity even with the coming of the digital age?

Trip: I’m not surprised, because they’re so much more social. There’s something about a group of people, around the same table, being fully present, having table talk or trash-talking, being able to recognize body language and facial expressions, and having other kinds of casual and social interactions.

Mollie: If your son’s school, instead of having a Sadie Hawkins dance, had a Trip Hawkins dance, what would that be like?

Trip: It’s funny. I have an aunt whose nickname was Sadie, because of the Sadie Hawkins dance. [laughs] I suppose the Trip Hawkins dance would have to have a lot of Dance Dance Revolution units and definitely some competition around some of the dancing-game mechanics.

Mollie: What flavor of chocolate is Digital Chocolate?

Trip: You know, it’s actually probably dark chocolate, because there was such a strong European influence throughout the history of the company.

Mollie: What was one point in your life where you failed the real-life equivalent Dungeons & Dragons saving throw, and you wish you could go back and re-roll?

Trip: I think it’d be the moment where, in the early days of 3DO, I talked to Sony when they weren’t really far along at all [on the development of the PlayStation]. We hadn’t built our machine yet, but we had a design, we had a prototype, and we were going to be in production with our chips well ahead of Sony; that was a moment where nobody really knew if Sony was serious or not about games. I guess I would’ve liked to have either asked Sony to join forces and be partners with what we were doing—just do it together, instead of later finding out that you’re going to be competing—or I would’ve liked to have understood at that moment enough to realize, “Wow, Sony’s really serious about this, and they’re going to do a much better job, and I should just stop trying to do it with 3DO. There’s no point.” [laughs] That would’ve saved a good decade of my life.

Photography credit: David Calvert